Top: Tea Partyists protest at the US Capitol during the federal budget stalemate in 2011 (photo by William Westermeyer). Bottom: An Israeli army checkpoint in the West Bank.

Top: Tea Partyists protest at the US Capitol during the federal budget stalemate in 2011 (photo by William Westermeyer). Bottom: An Israeli army checkpoint in the West Bank.

Summary

“Culture and Political Subjectivities” is a two and a half day workshop on anthropological approaches to political subjectivities. “Political subjectivities” are thoughts, feelings, motivations, identities, and memories, not just about electoral politics, but more broadly regarding public policy and disputes over the social distribution of power, status, and economic rewards. While many anthropologists have studied these topics, this workshop is unusual in bringing together psychological anthropologists and interlocutors in related fields who are concerned with complexities in the social and psychological processes by which political subjectivities are formed in cultural contexts. Workshop participants have been examining the formation of political subjectivities through ethnographic research on topics such as skepticism about the science of climate change in Oklahoma, Israeli soldiers’ changing moral positions about their actions in the Occupied Territories, the personal projects of local Tea Party leaders, precursors to conversion to Salafi forms of Islam in northern Nigeria, xenophobia in Scandinavia, the political outlooks of the long-term unemployed in the United States, the development of Rastafarian political identities in Jamaica, and how middle-class transsexuals in India decide to become public activists.

This workshop will be focused around three general thematic topics that will leverage the different theoretical, analytical, methodological, and ethnographic/regional specialties represented by our invited workshop participants. These topics encompass three, broad sets of questions:

1. What is the relation between publicly expressed political discourses, on the one hand, and personal experiences, affects, or understandings, on the other? Are there any gaps or disjunctures between collective political ideologies and individuals’ ways of making sense of political disputes?

2. What are different forms of political consciousness? What sorts of conflicts are there between explicit identities and outlooks, on the one hand, and tacit or unconscious or embodied ones, on the other?

3. What leads people to join social movements and form senses of themselves as movement actors? How do their personal experiences, affective commitments, and social networks affect the specific nature of their activism?

“Culture and Political Subjectivities” is a two and a half day workshop on anthropological approaches to political subjectivities. “Political subjectivities” are thoughts, feelings, motivations, identities, and memories, not just about electoral politics, but more broadly regarding public policy and disputes over the social distribution of power, status, and economic rewards. While many anthropologists have studied these topics, this workshop is unusual in bringing together psychological anthropologists and interlocutors in related fields who are concerned with complexities in the social and psychological processes by which political subjectivities are formed in cultural contexts. Workshop participants have been examining the formation of political subjectivities through ethnographic research on topics such as skepticism about the science of climate change in Oklahoma, Israeli soldiers’ changing moral positions about their actions in the Occupied Territories, the personal projects of local Tea Party leaders, precursors to conversion to Salafi forms of Islam in northern Nigeria, xenophobia in Scandinavia, the political outlooks of the long-term unemployed in the United States, the development of Rastafarian political identities in Jamaica, and how middle-class transsexuals in India decide to become public activists.

This workshop will be focused around three general thematic topics that will leverage the different theoretical, analytical, methodological, and ethnographic/regional specialties represented by our invited workshop participants. These topics encompass three, broad sets of questions:

1. What is the relation between publicly expressed political discourses, on the one hand, and personal experiences, affects, or understandings, on the other? Are there any gaps or disjunctures between collective political ideologies and individuals’ ways of making sense of political disputes?

2. What are different forms of political consciousness? What sorts of conflicts are there between explicit identities and outlooks, on the one hand, and tacit or unconscious or embodied ones, on the other?

3. What leads people to join social movements and form senses of themselves as movement actors? How do their personal experiences, affective commitments, and social networks affect the specific nature of their activism?

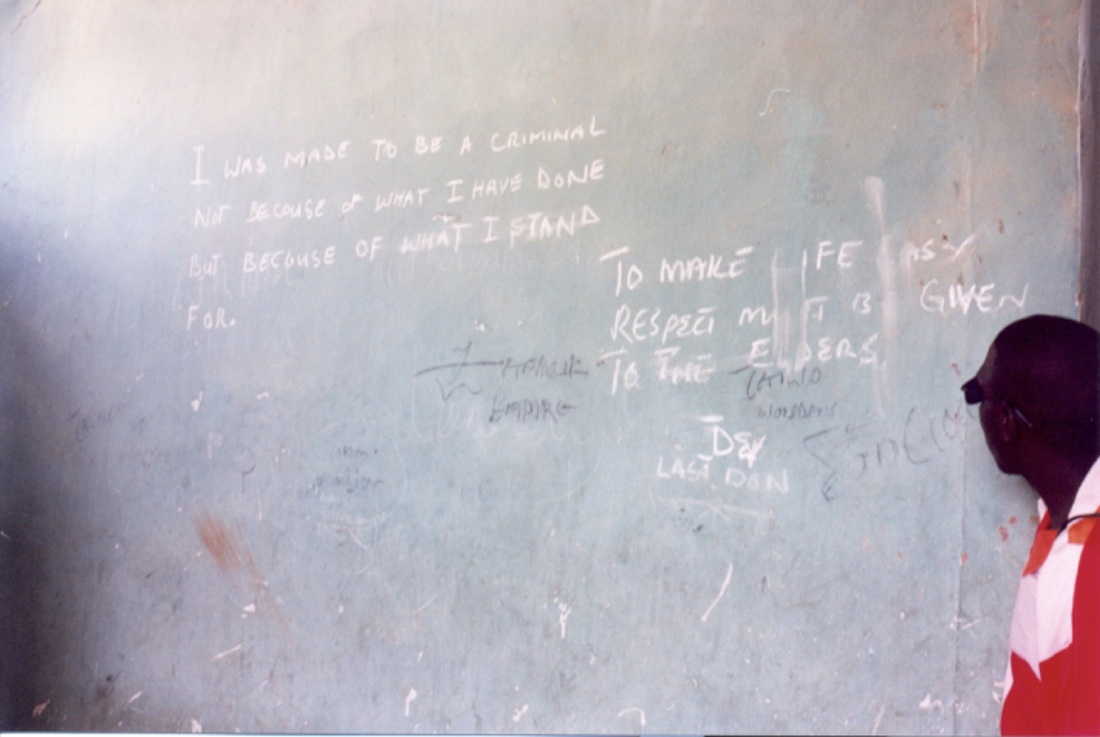

Graffiti by Urban Gang Members, Kano, Nigeria, 2004 (photo by Conerly Casey).

Graffiti by Urban Gang Members, Kano, Nigeria, 2004 (photo by Conerly Casey).

Why Psychological Anthropology and Political Subjectivities?

The workshop will be structured to facilitate dialogue among scholars representing different paradigms within psychological anthropology as well as between psychological anthropologists and researchers studying political subjectivities in political anthropology and other disciplines.

Within psychological anthropology, cultural models research produces careful descriptions of people’s mental representations, while identity-in-practice researchers tend to pay less attention to those, but more to the local contexts of thought, especially those that are contentious. Psychodynamic anthropologists focus on the way subjectivities can derive not just from practical projects or learned schemas but also from unacknowledged psychic needs. Insights into a given topic (e.g., anti-immigrant sentiments, which are studied by several workshop participants), would be enriched by being challenged by scholars with alternative perspectives, including some not listed above, such as those associated with evolutionary psychology (Hirschfeld 1998).

Regarding dialogue between psychological anthropologists and those in other fields, we see the potential for intellectual cross-fertilization with scholars who work in political anthropology, political sociology, and political psychology.

The workshop will be structured to facilitate dialogue among scholars representing different paradigms within psychological anthropology as well as between psychological anthropologists and researchers studying political subjectivities in political anthropology and other disciplines.

Within psychological anthropology, cultural models research produces careful descriptions of people’s mental representations, while identity-in-practice researchers tend to pay less attention to those, but more to the local contexts of thought, especially those that are contentious. Psychodynamic anthropologists focus on the way subjectivities can derive not just from practical projects or learned schemas but also from unacknowledged psychic needs. Insights into a given topic (e.g., anti-immigrant sentiments, which are studied by several workshop participants), would be enriched by being challenged by scholars with alternative perspectives, including some not listed above, such as those associated with evolutionary psychology (Hirschfeld 1998).

Regarding dialogue between psychological anthropologists and those in other fields, we see the potential for intellectual cross-fertilization with scholars who work in political anthropology, political sociology, and political psychology.

Environmental activism in North Carolina, 2015 (photo by Dorothy Holland).

Environmental activism in North Carolina, 2015 (photo by Dorothy Holland).

Broader Impacts

Although the focus of this workshop is on the theoretical contributions, it is also notable that the research of the workshop participants concerns very important, current public policy issues both in the United States and elsewhere. The workshop and the published workshop proceedings should attract considerable interest for the research topics of workshop participants, which include Muslim conversion in Africa, anti-immigrant tension in Scandinavia, the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, and skepticism about climate change science and the attraction of Tea Party politics in the United States. Our research highlights the psychological complexities in the development of political subjectivities in these arenas.

The research of participants in this workshop reveals that grassroots political subjectivities are often not as polarized as the ideologies of political leaders (Strauss 2012). Publicizing these findings may help heal the divisions that have marked contemporary political life in the United States and many places around the world. Tanya Luhrmann, another psychological anthropologist, provides a model for our work, in this regard. In invited columns in The New York Times she attempts to bridge the gap between secular liberals and religious conservatives by helping readers understand some of the cultural belief systems and psycho-cultural models that guide contemporary evangelical Christian communities in America. By drawing on her scholarly research at the intersection of culture, psychology, religion, and politics, Luhrmann provides a model for the broader impacts of the proposed workshop.

Although the focus of this workshop is on the theoretical contributions, it is also notable that the research of the workshop participants concerns very important, current public policy issues both in the United States and elsewhere. The workshop and the published workshop proceedings should attract considerable interest for the research topics of workshop participants, which include Muslim conversion in Africa, anti-immigrant tension in Scandinavia, the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, and skepticism about climate change science and the attraction of Tea Party politics in the United States. Our research highlights the psychological complexities in the development of political subjectivities in these arenas.

The research of participants in this workshop reveals that grassroots political subjectivities are often not as polarized as the ideologies of political leaders (Strauss 2012). Publicizing these findings may help heal the divisions that have marked contemporary political life in the United States and many places around the world. Tanya Luhrmann, another psychological anthropologist, provides a model for our work, in this regard. In invited columns in The New York Times she attempts to bridge the gap between secular liberals and religious conservatives by helping readers understand some of the cultural belief systems and psycho-cultural models that guide contemporary evangelical Christian communities in America. By drawing on her scholarly research at the intersection of culture, psychology, religion, and politics, Luhrmann provides a model for the broader impacts of the proposed workshop.

The Water Wars in the U.S. southern plains and west, Sardis Lake, Oklahoma, 2014 (photo by Jack R. Friedman).

The Water Wars in the U.S. southern plains and west, Sardis Lake, Oklahoma, 2014 (photo by Jack R. Friedman).

Additional policy impacts are envisioned associated with this workshop. For instance, one of the workshop organizers, Friedman, is currently part of an interdisciplinary team studying both attitudes about climate change science and the climatological, meteorological, hydrological, and ecological changes that are occurring in Oklahoma (“Adapting Socio-ecological Systems to Climate Variability,” NSF-IIA-1301789). He notes that his natural science colleagues become frustrated by contradictions in the views of the public and say, “all we need to do is to better educate people” and they will become conscious of the “error of their ways.” This naïve understanding of the ways in which social organization, politics, economic structures, cultural knowledge, and psychology intersect has tended to lead to a cycle of frustratingly unproductive (and, frankly, wasteful) interventions. We seek to operationalize the various theoretical, analytical, and methodological approaches shared in the workshop in order to improve the ways in which decision support can be provided to both planners and regular people faced with real-world challenges like those associated with the consequences of severe climate variability in Oklahoma.

Broadly, the research of workshop participants contributes a much more sophisticated way of understanding political subjectivities and the development and implications of stances toward political issues and, even more significantly, of identities or senses of self as an actor in a political struggle. The approaches to be discussed and disseminated can help governmental, non-governmental, grassroots, and community-based decision makers avoid falling back on the reliance on vague notions of “public education” in order to improve how messages can be provided to the public. We believe that, like Luhrmann’s recent public anthropology, the theoretical models of political subjectivity that will emerge from this workshop will provide decision makers with tools to understand the complexity of people, allowing them to better do their jobs as representatives of the people, and ensuring that public concerns are addressed.

Broadly, the research of workshop participants contributes a much more sophisticated way of understanding political subjectivities and the development and implications of stances toward political issues and, even more significantly, of identities or senses of self as an actor in a political struggle. The approaches to be discussed and disseminated can help governmental, non-governmental, grassroots, and community-based decision makers avoid falling back on the reliance on vague notions of “public education” in order to improve how messages can be provided to the public. We believe that, like Luhrmann’s recent public anthropology, the theoretical models of political subjectivity that will emerge from this workshop will provide decision makers with tools to understand the complexity of people, allowing them to better do their jobs as representatives of the people, and ensuring that public concerns are addressed.